|

Conf: Trespassing Walls: Jews, Christians, and Muslims around their Texts and Traditions Introduction: Research attempting to bring down the walls between the three Abrahamic faiths rightly draw on their shared historical and philosophical developments within Aristotelianism and Classical Theism. These attempts frequently present a paragon thinker from each faith, or at least the most renowned, namely: Averroes (d. 1198), Moses Maimonides (d. 1204), and Thomas Aquinas (d. 1274). Since Averroes may have influenced Maimonides and both Averroes and Maimonides clearly influenced Aquinas, this trio allows for the tracing of philosophical ideas across time and faith. However, other than historical precedent, the selection criterion used to arrive at these three thinkers is not readily apparent, or at worst, reflects an Orientalist mentality beginning with Aquinas and moving to the non-Christian thinkers he relied on. Since Aquinas, Maimonides, and Averroes hold differing methods to certain knowledge which result in very different philosophical schemas, I argue for an alternative selection criterion based on a key epistemological limit to group likeminded thinkers across the three Abrahamic traditions. The selection criterion I propose is what I term the “epistemological wall” or the end of reason. Thinkers who allow divine testimony to go beyond reason’s limits fall into one camp I am calling “limited rationalism” while the alternative camp of “strong rationalism” refers to thinkers who perceive reason as the sole path to knowledge either by rationally demystifying divine prophecy or allowing no room for supernatural guidance. In what follows, I will elaborate on the distinction between the “strong” vs. “limited rationalism” epistemological methodologies. Afterwards, I will show that the traditional trio of Averroes, Maimonides, and Aquinas draws from both methodologies while overlooking the difference. Then I will propose alternative sets of thinkers based on the selection criterion of the “epistemological wall”, focusing mainly on limited rationalists who allow divine testimony to trespass this epistemic wall to obtain certain knowledge, namely Saadya Gaon, al-Ghazali, and Thomas Aquinas. Strong vs. Limited Rationalism In distinguishing the difference between what I am referring to as strong and limited rationalism, the “epistemic wall” should become apparent. “Strong rationalism” refers to the idea that Aristotelian science (“reason”), as outlined in Posterior Analytics 1.2, is the sole path to certain knowledge.[1] While recent Aristotle scholars have suggested that Aristotle likely had in mind a weaker notion such as “understanding”, here I refer to the Aristotelian tradition following al-Kindi’s goal to develop a philosophy that could rival the certainty of mathematics, a hard episteme in which knowledge is certain. The method to obtain certainty is thus based on Aristotle’s metaphysics, in which a validly formed demonstrative syllogism built on true premises necessarily yield true conclusions.[2] When demonstrative knowledge contradicts revealed religious knowledge, the apparent sense of the religious law must be reinterpreted to fit the demonstrative conclusion or accord with double-truth (i.e., holding to two contradictory truths, one taught by philosophy and one commanded by faith). Since Aristotelian demonstrative knowledge is the strongest and most certain form of knowledge, any claim unproveable by reason cannot obtain certainty, and if certainty equals knowledge, then such claims are effectively unknowable. This limit or end of reason is the “epistemic wall.” “Limited rationalism” refers to epistemological methods that accept the strength of Aristotelian scienc but trespass the “epistemic wall” by asserting that knowledge beyond demonstration is possible by another means, typically labeled “faith”. The end of reason is not the end of knowledge since demonstration is not the only way to certain knowledge. Such extra-demonstrable knowledge typically comes through God’s testimony (assertions from an omniscient and trustworthy being) in the form of revelation or religious law making it “certain” knowledge which compliments natural reason. While some knowledge is only obtainable via one method or the other, faith and reason are not mutually exclusive and can reach the same conclusions. Hence, allowing the methods to complement one another provides the most expansive epistemological picture. Strong rationalists often took issue with such “faith”-based approaches by accusing speculative theologians, such as the Mutakallimun, of incorporating revelatory premises unproven by natural causes or reason into their demonstrations or using reason post hoc to explain presupposed religious opinions. The fear is the methods of limited rationalism render reason subservient to revelation, not its complement. Alternative Trios based on the Epistemological Wall Alternative Strong Rationalist Trio: Maimonides, Averroes, and Siger Brabant Using the “epistemic wall” as the selection criterion, we can see that Maimonides and Averroes fit comfortably in strong rationalism (and as we shall see, Aquinas does not). A telling example is their explanations of prophecy, the primary medieval understanding of how God communicated non-demonstrable certainty. In brief, for Maimonides prophecy is a rational process, an emanation of an intelligible form from God via the causality of the Agent Intellect. Prophets require the necessary rational faculties to receive the intense degree of the intellectual emanation and the necessary imaginative faculties to concretely represent what they received intellectually. Averroes likewise describes a true prophet not as revealing knowledge beyond the limits of reason but making knowledge and laws known that “are in accordance with the truth and which bring about acts that will determine the happiness of the totality of mankind.”[3] As such, Religious Law must yield to philosophical demonstration when conflicts arise such that the apparent meaning must be reinterpreted in light of an “inner-meaning.”[4] For strong rationalists, prophecy is merely another form of rational knowledge using the same epistemology as science and metaphysics. So what Christian thinker could round out a trio of Abrahamic strong rationalists? I propose Siger Brabant (d. 1281) or his colleague Boetius of Dacia (d. 1284), professors of philosophy at the University of Paris. Both were contemporaries of Aquinas and they too were influenced by Maimonides and Averroes. These thinkers separated truths into two mutually exclusive modes: revealed truths known via a faculty of faith and rational truths known via Aristotelian logic. Boetius of Dacia even expressed the sentiment: “when someone puts aside rational arguments, he immediately ceases to be a philosopher; philosophy does not rest on revelations and miracles”.[5] Consequently, both Siger Brabant and Boetius of Dacia were swept up the 1277 Paris Condemnations of “Latin Averroism” for holding to double-truth. This reveals how strong rationalist epistemologies often ran afoul of religious orthodoxy.[6] A point confirmed by Kenneth Seeskin’s Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry regarding Maimonides which asks: “Is this the religion of the prophets or a philosophically sanitized religion concocted by a medieval thinker under the sway of Aristotle?” Seeskin’s answer: “Maimonides would reply that there is no difference.”[7] Alternative Limited Rationalist Trio: Thomas Aquinas, Saadya Gaon, and al-Ghazali In his Summa Contra Gentiles, Aquinas famously outlines a “twofold mode of truth” (duplex veritatis modus), between knowledge obtainable by philosophical principles vs. divine testimony commonly differentiated as “preambles of faith” and “articles of faith” respectively (not to be confused with “double-truth”).[8] In asserting that certain truths, such that God is triune, cannot be obtained by human reason but must be obtained by prophets acting as God’s instruments, Aquinas’s epistemology contains an “epistemic wall” placing him comfortably in limited rationalism. So what Jewish and Islamic thinker share a similar twofold approach to certainty that would round out a trio of Abrahamic limited rationalists? I propose Saadya Gaon and al-Ghazali. Saadya was a Jewish Gaonim (the Gaonim were directors of Jewish academies and spiritual leaders of the Jewish communities from 589-1038CE). Colette Sirat in his History of Jewish philosophy in the middle ages describes Saadya as being convinced that “Torah and science spring from the same branch; they cannot contradict each other in any way”.[9] Like Aquinas three centuries later, Saadya taught two acceptable approaches to knowledge: “laws of reason” (al-shari’a al-‘aqliyyât, or “rational/intellectual laws”) and the “laws of revelation” (al-shari’a al-sam‘iyyât, or “heard laws”), which together allowed for the dispelling of doubt.[10] “Laws of reason” apply to what any rational agent can deduce by drawing on the first three “roots of knowledge”: sense perception (eye-witness), reason (intuition of the intellect), and inference (logical necessity). For Saadya, reason needs revelation because of the epistemic wall. Hence, the “laws of revelation” apply to the fourth “root of knowledge” gained from the Torah or oral teachings, both referred to as “the trustworthy report” (al-khibar al-sadiq), which is frequently translated as “Authentic Tradition.”[11] The fourth root of knowledge is thus literally the “hearing” of “trustworthy reports” from God. Saayda thereby provides a perceptual account of prophecy that avoids anthropomorphizing God without falling into allegorism and psychologism but still maintains that the prophets really see and hear God via his Created Glory (kavod nibra) a “second air” which pervades the entire world and acts as a substrate or medium. Al-Ghazali was a Nizamiyya in Baghdad (the most prestigious and challenging professorial position appointed by the vizier). He likewise held to two methods of obtaining certain knowledge. The “highest” form immune to error comes from a form of religious experience known as dhawq (literally a “tasting” of the divine comparable to mushahada--“actual seeing and handling”). Dhawq is thus the most desired state since it allows one to personally verify what one knows. This subjective personal verification, or “perfection” (istikmal) is the only real difference between knowledge received through dhawq and achieved through apodictic proofs. Demonstration (burhan) also obtains certain knowledge (ilm), but is subject to doubt due to error. Thus, his portrayal of an “epistemic wall” is probably best seen in his infamous Incoherence of the Philosophers. However, the rarity of dhawq makes philosophical methods invaluable. Finally, those not capable of burhan can rely on belief or faith, the “favorable acceptance” based on “hearsay and experience of others” (taqlīd). Interestingly, knowledge obtained by testimony is the least certain for al-Ghazali and even prophets can only be trusted when their claims are verified by theoretical knowledge even going so far as to claim in al-Qistas al-Mustaqim that the Qur’an can be trusted since it provides syllogisms which conform to reason.[12] Thus, alGhazali claims that he “gives credence to the veracity of Muhammad and of Moses” not on account of their miraculous signs and wonders, but in the same way as one’s doubts about mathematics are dispelled by their teacher in arithmetic.[13] Like the trio with Maimonides and Averroes, these three thinkers were successive and represent medieval thought across the three Abrahamic faiths through three centuries (9th/10th Century – Saadya; 11/12th Century – al-Ghazali; 13th Century – Aquinas). Plus, their works were either available to or known to have been read and influenced one another (such as Aquinas’s use of al-Ghazali’s Maqasid in Latin translation). As shown above, these thinkers are also uniquely related in that they valued both reason and revelation, such that they desired to have sound rational explanations or arguments while maintaining orthodox formulations of the faith. As limited rationalist, they attempted to establish a middle ground between more heterodox philosophically or reason driven accounts embraced by thinkers such as Maimonides, Avicenna, and the “Latin Averroists” on one side, and more hardline faith-based approaches embraced by groups such as the Karaites, the Kalaamists, and the Augustinians on the other side. This is most clearly seen in their historical understanding of scriptural revelation as truths told by God himself, or God revealing through a rational account of testimony. Conclusion I have argued for an epistemological selection criterion, the “epistemological wall”, to divide thinkers who employ either “strong” or “limited rationalist” methodologies. After defining these two categories, I proposed alternative Abrahamic trios: Averroes, and Maimonides should be joined by Siger Brabant or Boetius of Dacia, while Aquinas should be joined by Saadya Gaon and al-Ghazali. This selection criterion better reveals how thinkers handled issues of knowing other than scientific demonstration, typically by incorporating revelation or divine guidance through God’s testimony. The relevancy of this criterion can still be seen today as famously expressed by Bertrand Russel who dismissed Aquinas as a philosopher since he did not “follow wherever the argument may lead” since to admit divine testimony did not qualify as a philosophic inquiry, but a “special pleading” for conclusions given in advance.[14] This selection criterion will hopefully not only more accurately present these thinkers, but direct meaningful epistemological investigations such as how limited rationalists can verify when an omniscient and trustworthy being (i.e. God) is speaking, or how strong rationalists can first learn the Aristotelian sciences without relying on the testimony of knowledgeable and trustworthy teachers. [1] W. By demonstration I mean a syllogism productive of scientific knowledge, a syllogism, that is, the grasp of which is eo ipso such knowledge. Assuming then that my thesis as to the nature of scientific knowing is correct, the premisses of demonstrated knowledge must be true, primary, immediate. better known than and prior to the conclusion, which is further related to them as effect to cause. Unless these conditions are satisfied, the basic truths will not be ‘appropriate’ to the conclusion. Syllogism there may indeed be without these conditions, but such syllogism, not being productive of scientific knowledge, will not be demonstration. (Posterior Analytics 1.2, 71b18-24, in Mure 1941, p. 112.) [2] Taylor, Rationalism. 229. [3] Averroes Incoherence of the Incoherence 1930: 516; tr. 1954: 316. See Taylor. Forthcoming. “Averroes and the Philosophical Account of Prophecy”. 6. [4] “In the face of conflict with the apparent meaning of the religious law, Averroes refused to assert the possibility of a double truth and instead insisted that the apparent meaning of religious law be recognized as incorrect and requiring interpretation of its inner meaning when in conflict with philosophical demonstration.” Taylor 232 [5] Boethius, and John F. Wippel. 1987. On the supreme good ; On the eternity of the world ; On dreams. Toronto, Ont. Canada: Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies. 65. [6] See Dales, Richard. 1984. “The Origin of the Doctrine of the Double Truth”. [7] Seeskin, Kenneth, "Maimonides", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2017 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2017/entries/maimonides/>. [8] SCG I. 3 “There is a twofold mode of truth in what we profess about God. Some truths about God exceed all the ability of the human reason. Such is the truth that God is triune. But there are some truths which the natural reason also is able to reach. Such are that God exists, that He is one, and the like. In fact, such truths about God have been proved demonstratively by the philosophers, guided by the light of the natural reason.” [9] Sirat, Colette. 1996. A history of Jewish philosophy in the Middle ages. 23. [10] Saadya makes this division in Treatise III on Commands & Prohibitions, even explicitly stating in chapter 3: “Now that I have expressed myself in this summary fashion about the two general divisions of the precepts of the Torah (al-shari’a), namely the rational (al-‘aqliyyât) and the revealed (al-sam‘iyyât), it behooves me to explain why there should have been need for divine messengers and prophets.” Saʻadyah, and Samuel Rosenblatt. 1976. The book of reliefs and opinions. 145. فاذ قد قلت هذه الجماه فى قسمى الشرائع وهما العقليّه والسمعيّه فينبغى ان ابين ما الحاجه الى رسل وانبياء And also: “Then I pondered the matter deeply and I found that there was considerable need for the dispatch of messengers to God's creatures, not merely in order that they might be informed by them about the revealed laws (al-shari’a al-sam‘iyyât), but also on account of the rational precepts (al-shari’a al-‘aqliyyât).” ثمّ تأملت النظر فوجدت حاجه الخلق الى الرسل حاجه ماسّه لا من اجد الشرائعالسمعيّه فقط ليعرفوهم اياّها بد من اجد الشرائع العقليّه [11] Rosenblatt consistently renders للخبرالصادق as “Authentic Tradition,” which is literally “the trustworthy report.” This is further strengthened by Saadya’s view that authentic revelation can come about only by means of prophecy. Saʻadyah, and Samuel Rosenblatt. 1976. The book of reliefs and opinions. New Haven, Conn: Yale Univ. Press. 63. وامّا نحن جماعه الموحّدين فنصدّق بهذه الثلاث موادّ التى للعام ونضيف اليها مادّه رابعه استخرجناها بالثلاث فصارت لنا اصلا وهى صحّه الخبر الصادق فانّه مبنىّ على الم للحسّ وعلم العقل كما سنبين فى المقاله الثالثه من هذا الكتاب | فصارت لنا اصلا وهى صحّه الخبر الصادق و الكتاب المنزله يحقّق لنا هذه ال اصول | انها علوم صحيحه لنه يحصى الحواسّ فى باب نفيها عن الوثان فيجعلها يعنم اليها اذ يقول [12] As a perfect example, al-Ghazali argues how it is logical that God sent the words of Qur’an upon mortal men: 1) Moses is a man; 2) Moses is one upon whom the Scripture was sent down; 3) Some man has had sent down upon him the Book [the Qur’an] Ibid., 300. [13] Ghazzālī, and David Pearson Brewster. 1978. The just balance: al-qistás al-mustaqim. SH. Muhammad Ashraf: Kashmiri Bazar Lamore, Pakistan. 72-73 [14] The critique mirrors that of Bertrand Russell’s contemporary critique of Aquinas: “There is little of the true philosophic spirit in Aquinas. He does not, like the Platonic Socrates, set out to follow wherever the argument may lead. He is not engaged in an inquiry, the result of which it is impossible to know in advance. Before he begins to philosophize, he already knows the truth; it is declared in the Catholic faith. If he can find apparently rational arguments for some parts of the faith, so much the better: If he cannot, he need only fall back on revelation. The finding of arguments for a conclusion given in advance is not philosophy, but special pleading. I cannot, therefore, feel that he deserves to be put on a level with the best philosophers either of Greece or of modern times” Russell, Bertrand (1945). A History of Western Philosophy. New York: Simon and Schuster. 463.

1 Comment

This is a handout which aggregates various views on creation from multiple sources (see citations) into one (relatively) compact handout.

This is a handout which aggregates various views on creation from multiple sources (see citations) into one (relatively) compact handout.

In Alvin Plantinga’s 1980 address to the American Catholic Philosophical Association “The Reformed Objection to Natural Theology”,[i] the proposition God exists is declared to be properly basic by the reformers and as a result natural theology—the arguments for God’s existence—is unnecessary. Following a brief summary of Plantinga’s paper, three benefits of properly basic beliefs will be outlined, and then three reasons will be presented as to why the complete rejection of natural theology using Plantinga’s account of properly basic beliefs simply goes too far.

Plantinga points out this conclusion by establishing that the Classical foundationalist approach of knowledge (commonly attributed to Plato through Aquinas and then a modified form to Descrates through the 20th Century) required all knowledge be built upon certain foundational propositions—namely those that are either self-evident, evident to the senses, or incorrigible—made natural theology necessary. However, reformers like John Calvin rejected Classical foundationalism (in lieu of a form of weak foundationalism) on the grounds that God exists is a foundational proposition per scripture but does not fit the requirements to be a foundational proposition (that is the existence of God is not self-evident, evident to the senses, or incorrigible). As a result, since theologians no longer need to work with foundational principles to arrive at the knowledge of God natural theology becomes unnecessary. Joseph Boyle’s response to Plantinga concisely captures the line of thought: “The Christian knows God exists. Natural theology makes sense only if God's existence is not in the foundations. But it is.”[ii] Abstract:Mark Alfano’s book Character As Moral Fiction[1] presents a clear and precise reflection on the situationist view promoted by Gilbert Harman and John Doris, and three of, what he claims to be, virtue ethic’s failed responses to their critique. After a brief overview of virtue ethics, situationism, and their current debate, this paper will argue that Mark Alfano’s objections to one of the responses to situationism, the “dodge,” are insufficient, and thus virtue ethics in its traditional form survives. Once it is shown that the evidence from situationism does not in fact disprove virtue ethics, ideas for ways forward will be proposed since if virtue ethics need not fear situationism, then it ought to embrace potential benefits from its findings. [1] Alfano, Mark. Character As Moral Fiction. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013. (a PDF can also be found in the Academic Section). An Unsatisfactory Kantian Compatibilism: A Critique of Allen Wood’s Approach to the Third Antinomy3/26/2014 Abstract: It is the aim of this paper is to show that Allen Wood’s compatibilism should ultimately be rejected since his view suffers from two major challenges, 1) the necessity of Intelligible causality for Empirical causality and 2) timeless agency. To do so this paper is comprised of two major sections: a survey of Kant’s stated position on how the third antinomy is actually an illusion since both freedom and determinism can both viably exist in Part I, and then a critique of Allen Wood’s theory on how best to interpret the compatibilism Kant achieves in Part II. This will show that the compatibilism Wood promotes, while not necessarily dissatisfactory as a coherent perspective, is ultimately unsatisfactory since it essentially disengages freedom from the natural world. (a PDF can also be found in the Academic Section). Most of my Spring Semester was consumed researching and writing this. Enjoy... (a PDF can also be found in the Academic Section). Abstract: By reviewing attempts by the Eastern Orthodox Church, the Roman Catholic Church, Evangelical Churches, Protestant Neo-Orthodoxy and the recent contributions of Speech Act theory on divine discourse to reconcile the two forms of the Word of God (The Written Word and the Living Word), this paper aims to address how the gap between mankind and the transcendent God can be bridged to allow for the proper order of metaphysics leading to epistemology without denigrating God’s Word by answering the question: is Christ as the illocution of God the essential link between ontology and epistemology, and thus the starting place for Christian systematic theology?  I. Howard Marshall's chapter on Revelation in terms of Dogmas, Doctrines, Distinctives, and Details.* Dogmas. Marshall balances hotly debated topics well and remains firm on the essentials, including God as the primary actor. Christ has “immense significance in the accomplishment of God's purpose for the world and for his people, but always under God” (550). Marshall affirms what he sees as a full Christology, that Christ is the “first and foremost witness and therefore the pattern and inspiration for his followers in the church,” resurrected from the dead, ruler of kings, the recipient of doxological address, and the redeemer/liberator by means of his blood (death on the cross) who will come again (550-551). Christ also receives language reserved for God pointing to his divine nature (561-562).  I. Howard Marshall's chapter on John in terms of Dogmas, Doctrines, Distinctives, and Details.* Dogmas. In John, Marshall rightly recognizes Jesus' claim to preexist Abraham and sees support for Christ claiming “parity with God,” but his insistence feels lacking in some areas (502). He accurately captures the main theme as Jesus is the Messiah and Son of God “who came into the world to bear witness to the truth and to give his life so that all people might have the opportunity of receiving eternal life through faith in him” (512). From here, Marshall wonderfully describes seven principal points that impact Christology, being the Logos's: 1) divine eternal nature, 2) responsibility for creation, 3) bringer of light (salvation), 4) rejection by the world, 5) human nature, 6) witnessed by disciples, and 7) the mediator of full blessing (492-493). These are summed up in Christ's role and status, where he is: God's sent one (implying that it is God's will and purpose to save the world), and the founder of salvation (not the “Revealer” so Bultmann or “mythological divine figure” so Ernst Kasemann) (512). The Bultmannian school is cast as only “superficially plausible” and “breaks down under closer inspection” since Salvation goes much deeper, being a “life in relationship with God” (520). This demands that “faith is not only an intellectual acceptance of the message, but also a total commitment of the person to Jesus and to God” since faith is a continuing relationship and not an aorist event (521).  'Kiss of Judas' by Giotto ca. 1304 'Kiss of Judas' by Giotto ca. 1304 Scot McKnight's The Warning Passages of Hebrews: A Formal Analysis and Theological Conclusion article in terms of Dogmas, Doctrines, Distinctives, and Details.* Dogmas. McKnight himself asserts that “virtually all commentators and theologians can agree” that Hebrews promotes perseverance in light of eternal punishment (36). All Christians can affirm that “Perseverance is a necessity for those who are God's people” (32), since, whether or not one can lose their salvation, those who are truly saved persevere in faith. Those who don't persevere are either false believers (unregenerate) or in McKnight's view, “lose their faith” (58). Either way, the result is the same: Persevering faith is key to God's plan. Furthermore, McKnight affirms the orthodox Christian belief for the lack of perseverance, “that those who do not persevere until the end will suffer eternal punishment at the expense of the wrath of God” (36).  I. Howard Marshall's chapter on Ephesians in terms of Dogmas, Doctrines, Distinctives, and Details.* Dogmas. Marshall sees support for the Holy Spirit as a “personal being rather than an impersonal power” since in Ephesians 4:30 the Holy Spirit is able to be grieved by human conduct (387). He also affirms the vital role of the Holy Spirit in the life of the believer throughout Ephesians (395). Doctrines. Marshall makes reference to the Moral Example theory of Atonement as unsupported by Ephesians 5 (which supports human forgiveness as requiring divine forgiveness) since “Christian teaching on behavior was continually buttressed by central theological statements” to the point that they were made “almost causally in an ethical instruction” (387).  Stewart unabashedly demands that preachers see themselves as more than a talking head for 30 or so minutes on Sunday morning. He wishes to overcome the cultural “inclination to regard the preacher as the purveyor of religious homilies and ethical uplift” and replace it with its original intent, “the herald of the mighty acts of God” (16). His opening chapters reveal that preaching is an eternal art in the dual sense that it has been carried on by men to the present day since Christ walked the Earth, and that its impacts are eternal in the future! For preaching should revolve around one theme and one theme only, the saving Gospel of Jesus Christ. Stewart claims that “the basic message thus remains constant and invariable,” but in the face of an ever changing world “our presentation of it must take account of, and largely conditioned by, the actual world on which our eyes look out today” (11). This sets the stage for the rest of the book, which covers the means by which the Gospel is to be proclaimed. His style and authority feel timeless, putting modern authors to shame, as he rightfully reestablishes the critical importance of preaching the message of Christ “in and out of season.”  August 2007 Cover Simon Gathercole's What Did Paul Really Mean? article in terms of Dogmas, Doctrines, Distinctives, and Details.* Dogmas. Since the New Perspective focuses narrowly on what Paul says about Justification, which strikes at the heart of Soteriology (the means by which God planned to save mankind), it must be taken seriously. The issue is when the New Perspective is applied to Paul as his dedication “to warning against exclusivist national righteousness” (25) to the destruction of Justification. Gathercole does well critiquing the new perspective while saying that Jews still need to hear the gospel. The crux of his argument is rightfully “Christian faith” not as an add on to life, but something that “requires a complete reorientation of our whole attitude” and “response to God's specific promises” (27). His conclusion describing “what kind of faith” the bible defines and “what is wrong with works of the law” deserves a hearty “amen!” as he stresses that Paul “stresses that God is the sole operator in salvation” (28). Ultimately, he hits the nail on the head by stating that “true unity comes not at the expense of doctrine, but precisely around the central truths of the gospel” (27).  I. Howard Marshall's chapter on Romans in terms of Dogmas, Doctrines, Distinctives, and Details.* Dogmas. Marshall strongly affirms that Paul's main them in Romans in none other than the Gospel of Jesus Christ's ability to save and the subsequent answer to “Why?”. He thus affirms Paul's explanation that all people are sinners since “failure to acknowledge God leads to sinfulness” (308). This is the result of Original sin as revealed by the Law (since its role in salvation history is not a means of getting “right with God by observing the law” (309)). Salvation is portrayed as exclusively available through justification by grace through faith in Christ, whose blood was shed on the cross for sin since “to be justified is to be put into a right relationship with God, in which the sins that persons have committed are no longer counted against them and consequently they can enter into a relationship with God characterized by peace and not wrath” (310). Resurrection is indicated as “an integral part of the saving event and not just simply the restoration of Jesus to life...” after dying for sin (313). Universalism (via postmortem persuasion, etc.) is dismissed as textually unsupported (339).  Purposes and goals of pastoral counseling. Before stating the purpose or goal of pastoral counseling it is important to define what pastoral counseling is. The easiest way to approach a definition is to narrow the field by identifying what pastoral counseling is not since many activities aid Soul Care, or spiritual growth toward Christian sanctification. At its broadest levels, Christian Friendship can be provided by friends and family to encourage deep growth and healing (Benner, 17). Pastoral ministry includes “anything that brings people into contact with God nurtures the growth of their spirits and heals their souls” (Benner, 18), but is often stunted to maintain all pastoral roles. The Great Commission is impossible, but Jesus gave a phenomenal promise that the Church can succeed: "Behold, I am with you always, to the end of the age" (Matthew 28:20), Christ's perpetual presence. There are three implications of Christ's perpetual presence that allow us to proceed with the Great Commission with confidence: 1. Commission Impossible – we need help 2. Divine Supervision – we are not abandoned 3. Mission Accomplished – there is an end Stylistic question: some people love audience involvement (aka. "repeat after me" or "turn to your neighbor and say..." etc.) and some people hate audience involvement. Is there a right way to do it? Should it be done at all?

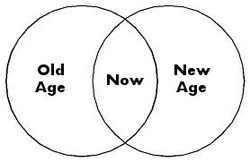

Escahtological Dualism - Already/Not Yet Don Howell's "Pauline Eschatological Dualism and its Resulting Tensions" in terms of Dogmas, Doctrines, Distinctives, and Details.* Dogmas. Many of the attributes, or defining characteristics, of this present age and new age (regardless of the understanding of their relationship to one another) are Dogma level issues including: sin as a dominating force of the present age as both “human solidarity with Adam” in original sin and sin “as individual acts of rebellion against God's will” which have the inevitable consequence of death physically or spiritually (13); new life as the replacement or removal of the reality of sin as the believer is incorporated into Christ (14). Howell rightly rejects the idea that “Jesus had mistakenly expected or proclaimed the imminence of the Kingdom (5). For any position, such as A. Sweitzer's, that sees Jesus' proclamation as failure not only negates Christ's mission, but also his deity.  I. Howard Marshall's chapter on Galatians in terms of Dogmas, Doctrines, Distinctives, and Details.* Dogmas. Paul's reason for writing the letter to the Galatians deals with the very heart of the Gospel and thus most of the concepts fall under Dogma. Marshall clearly articulates the Gospel presented in the letter as how “a person could be put right with God or enter into a right relationship with him or be counted as 'righteous' only through believing in Jesus Christ and not by observance of the Jewish law” (215). Furthermore, Marshall promotes that there was one solid understanding of the Gospel as shared by all the Apostles and dismisses theories by Baur that Paul and Peter were rivals with a different understanding of the Gospel (215). He also affirms Paul's separate divine calling that was approved by the Apostles and the church in Jerusalem as a historical event, therefore in acceptance of Christ's theology (214). Hence, it is right to see the purpose of the Law not as an alternative way of life or means of salvation, but “to lead people to Christ by making them realize that they were sinners” (218).  Significant elements about the practice of soul care. The most important place to begin Soul Care is with God's revealed knowledge about man, which, according to scripture, is holistic, viewing man as one with many parts (53). Man is thus an integrated whole of which soul, body, and spirit reflect aspects of, so Man is an “embodied soul,” or an “inspirited body,” not a spirit animating flesh (22). Soul Care must therefore treat all three aspects of man, lest concern for the whole person be neglected (23). This is often times the failing of modern psychology, since “humans have often been stripped of all that made them distinctively human” (55) and seen as nothing more than a compilation of behaviors and models. Therefore, Benner asserts two aspects to Soul Care: cure, as “the response to the need for a remedy for sin”; and care, as “assistance in spiritual growth” (28) as they play out via various forms. Essentials & Non-Essentials: Confidence in the Spirit as Governing Ethos of the Pauline Mission1/8/2013  Don Howell's "Pauline Thought in the History of Interpretation" in terms of Dogmas, Doctrines, Distinctives, and Details.* Dogmas. Howell indirectly affirms the Holy Spirit as the third person of the Trinity and directly asserts the necessary role of the Holy Spirit in a person's salvation through conviction, conversion, sanctification, and wise exercise of Spiritual gifts (214). Doctrines. Howell affirms Roland Allen's assessment that missionaries and church planters often lack “confidence in the Holy Spirit to build the church” (203), but Paul called his converts to rely on the Holy Spirit to live out their faith rather than on his direction (204). Similarly, “he trusted the Spirit to guide the leaders in their oversight of the church” (204), for any church not led by the Holy Spirit is a cult, being led either by man or an alien spirit.  Full version with citations is attached to bottom of post. The Historical and Philosophical Context of Robert Funk Robert W. Funk (1926-2005) was a New Testament scholar in America with tremendous impact on his generation. He studied at Vanderbuilt University where he learned to use, and appreciate, form criticism and Rudolf Bultmann's existential approach to interpreting the New Testament. Funk was steeped in the theology of Bultmann, even translating Bultmann's two-volume Theology of the New Testament into English.i As a result, Funk's theories build off Bultmann's redefinition of biblical terms.  I. Howard Marshall's chapter on Acts in terms of Dogmas, Doctrines, Distinctives, and Details.* Dogmas. Marshall affirms all the central beliefs of Acts, starting with the Gospel message (155), which can only positively be responded to with repentance and faith for the forgiveness of sins (176) “expressed in submission to baptism” (181). The Trinity is emphasized, even though it is not specifically labeled as such (161). Furthermore, the exclusivity of Christ is strongly emphasized, so that not even Judaism is enough (161) stating that “Nobody else or nothing else can save, and no supplementation or prior conditions are needed” (164). Marshall also denies works righteousness, that keeping the Law can't save for salvation is by grace/faith (163). Marshall even touches on the Gospel in light of those who've never heard, stating that God “...has appointed the life of the nations in such a way that people should be able to find him without falling into idolatry” (167). Overview:

An analysis of Christ's Mission in Matthew 16:13-28 will help Christians to examine what influences their theology. There is too much in this passage to cover in 20 minutes, so a narrow focus is drawn from the parallel situation in Christ's day about maintaining a proper perspective and putting priorities straight in light of the Mission of God and the politics of the day. Christians need to ensure that political stances and agendas are the direct result of biblical principles in light of Christ's Mission and not culturally conditioned preconceptions supported with a smattering of proof-texts lifted from random parts of the bible. Preached on election day, 11-06-12. |

AuthorBrett Yardley: Categories

All

Archives

January 2019

|

||||||||||||